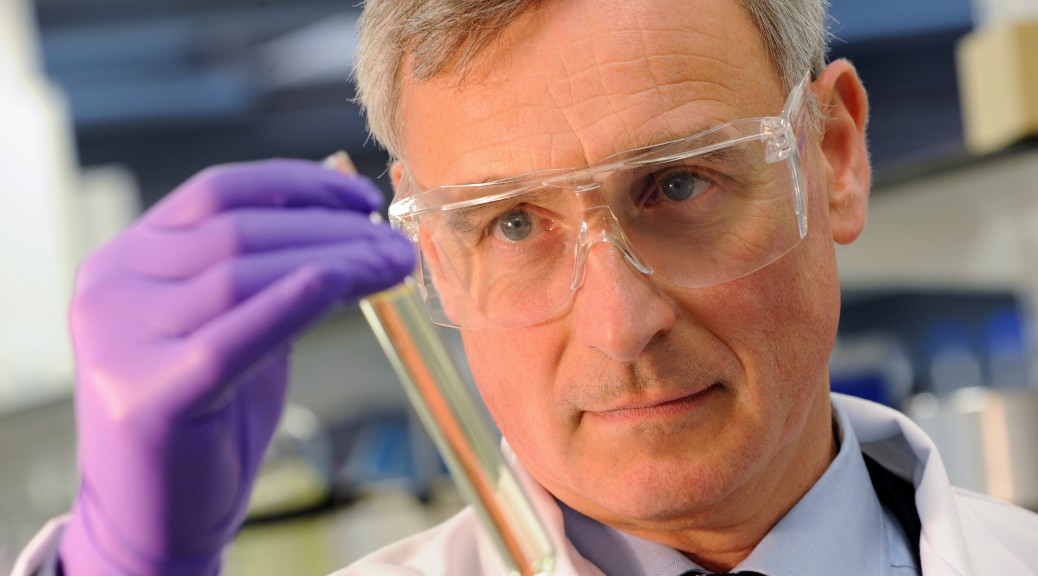

Chris Martin, Chief Executive of Sciona, a company at the cutting edge of business innovation and the revolution in genetics.

SMF Chris Martin is a highly qualified chemical engineer. His MBA demystified the workings of corporate finance and enabled him to pursue his ambitions for commercialising technology. Chris, who started his career as a chemical engineer, has harnessed the knowledge he gained from an MBA at leading Swiss business school IMD (formerly IMI) to combine his natural commercial flair with his scientific know-how. His sector is one of the freshest business areas to have opened up in the last decade – taking technology developed in academic institutions to mainstream markets.

Sciona, the latest in a string of spin-out ventures Chris has presided over, is leading the push to bring the benefits of major breakthroughs in mapping the human genome, to consumers.

His company offers a service to customers that reveals if they are genetically predisposed to illnesses affected by lifestyle factors like stress, diet and exercise. It offers consumers the opportunity to tailor their lifestyles to ensure prolonged health and well-being. Customers simply take a swab from inside their mouths that is then analysed by the company’s expert team of leading scientists to produce each individual’s unique genetic make-up. Combined with a brief lifestyle questionnaire, Sciona can advise its customers how best to make lifestyle changes to enhance their well-being.

Chris’ career started with a degree in Chemical Engineering at Aston University. He followed it with a DPhil in Engineering Science at Oxford University. It was during 18 months of post-doctoral work at the University and the Atomic Energy Research Establishment that he first started to develop his commercial instincts, starting a computer software company with his flatmates. Chris recalls, “I got a real taste for the commercial world and realised I enjoyed that side of the industry as much as the technical elements.”

He joined a small consultancy working in the offshore oil industry that then diversified into the pharmaceutical sector and other process engineering industries. “I took a diploma in management studies to try to understand more about business. From my work I thought I could see situations where large companies were making poor technology investment decisions.”

His interest in this subject grew and in 1988 he applied to Sainsbury Management Fellows for a place on the International MBA programme, opting for a one-year course at the leading Swiss business school IMI, now IMD.

Chris says, “Mine was a classic MBA, very strong on international finance and organisational development. The key thing was that the course demystified a lot of aspects of business. One of the biggest advantages my MBA gave me was a thorough understanding of corporate finance.”

After completing the course Chris used his new skills to tackle the trend of poor technology decision-making he had spotted over the previous years. He and a partner set up the consultancy as part of Marex in late 1989.

Early success, including a series of contracts from Courtaulds, was followed by Chris leading a management buy-out of the consultancy to form Paras Ltd. Growth over the ensuing years created a team of 40 professionals at offices in the UK, Holland and South Africa.

In the early 90s Chris’ attention turned to the growing trend of companies formed around technologies from leading universities and industrial research. He joined a fellow engineer to set up an early stage feed capital company after recognising that embryonic companies founded on campus research required expert outside help.

Chris and a growing number of expert colleagues created a string of successful technology companies including Solcom, which develops web-enabled systems monitoring and management systems, Despatch Box, a data encryption and security company, and SpiroGen, a biotech spin-out developing the technology to stop cancer cells replicating by binding specific DNA strands.

But it was Sciona and its potential for putting a truly groundbreaking health product in the hands of ordinary people that really fired Chris’ imagination. “It’s a really fascinating area to be working in, with some tremendously talented people.

“I’ve never been a traditional chemical engineer but the scientific foundation combined with the skills and knowledge I gained through my MBA have enabled me to take my career forward in challenging and, I hope, innovative ways.”

He concludes, “Every day I see that there is a significant change in the UK climate for entrepreneurial innovation. There are now a lot of well-educated, ambitious young people using their technical education to launch themselves into business. When the SMF scheme started more than dozen years ago, this was almost unheard of.”

You may also be interested in reading interviews with the winners of the SMF MBA Scholarship.